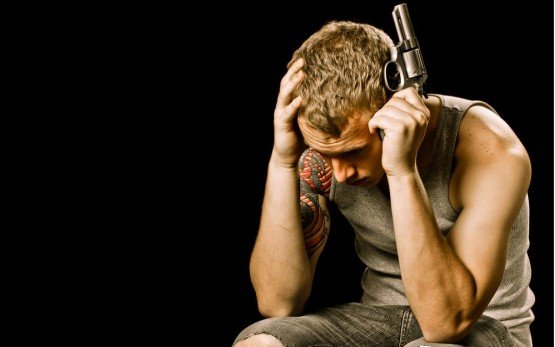

In my twenty-five years as a psychotherapist, I have probably had more conversations and thoughts about suicide, this week, than any other one-week period of my career. Robin Williams’ death by suicide no doubt brought up quite a lot of things, in quite a number of people. I suspect it goes beyond suicide itself.

Just today, I ran across a fascinating passage in an article on the subject:

Suicide is not a solution and does not create peace or freedom, as some would like to believe. The suicide of Robin Williams left us stunned, pained and saddened. For those closest to him, the pain is even more intense; suicide always hurts other people, particularly those closest to the person.

Nor is suicide an easy way out, a sign of weakness or a cowardly path, as still others would claim. Suicide is caused by what suicidologist Edwin Shneidman called “unbearable psychological pain,” the work of a vicious “anti-self” that goes against a person’s basic instinct to stay alive…

… Individuals who attempt or die by suicide are listening to what my father psychologist Robert Firestone refers to as the “critical inner voice” or “anti-self,” which berates them and lures them into their ultimate destruction. This internal enemy exists within all of us. Yet to some, particularly those who struggle with depression, addiction or other mental health disorders, this enemy can be life-threatening. In truth, it can be life threatening to any of us who succumb to its self-destructive directives. [Source: Lisa Firestone, Ph.D., writing at psychologytoday.com]

Perhaps one way to understand suicide is to understand why people don’t do it, even when they feel like they want to do so. The most common reason I have ever heard for not following through with suicide is: “I can’t do that to a loved one.” “Loved one” might refer to one’s young children; one’s grown children; one’s spouse; one’s circle of friends; one’s parents or siblings; even one’s pets or work associates have been offered to me as examples.

Some people have asked about Robin Williams, “How could he do that to his loved ones?” Or: “Where was his empathy?”

This passage contains part of the answer. Suicide is the ultimate and most definitive act of self-sacrifice one could ever imagine. If you hate yourself, and see yourself not fit for existence, of what relevance are the ones you love? How can you live solely for others while loathing oneself and life? In your self-loathing mindset, they’re frankly better off without you. To love is to value, and valuing always implies an “I.”

This hints at the great contradiction found in almost every ethical system to which all of us have ever been exposed. According to all civilized religions that I know about, suicide is unacceptable — perhaps one of the most mortal of sins imaginable.

Yet on an equal par with suicide, according to nearly all ethical systems, is any notion of self-interest, generally lumped into a philosophical-psychological package deal labeled “selfishness.”

Whenever there’s a dilemma between self-preservation and self-sacrifice, we’re taught to consider as unusual virtue the person who sacrifices, and to consider as less than noble (or downright bad) the person who watches out for himself.

Yes, we all watch out for ourselves on a daily basis, and some of us will reluctantly admit that’s OK — not really OK, but at least tolerable. Yet all of us are trained to feel that we really should be “giving back” which actually means — giving up, for the sake of giving up, for the sake of sacrificing what’s important to us personally and selfishly, precisely because it is important to us personally and selfishly.

Generosity is not considered a self-interested virtue. You’re supposed to be generous because it hurts, not because it brings you any pleasure. And you don’t possess worth other than by what you give to others. This is what everyone from the Pope to the President, to the modern equivalent of your Sunday School teacher, relentlessly pounds into our psyches.

Is it any wonder that depression and even suicide are widespread problems?

Other than criminal or sociopathic minds, virtually everyone I have ever been exposed to is horrified at the accusation of “selfish.” To be selfish means to be guilty of the greatest moral crime imaginable. This isn’t only true when you sacrifice another person to yourself (as in physical harm, or deceit); but whenever you take care of yourself, put yourself first for any reason, or act in your own interests — fully accepting the equal right and prerogative of others to do the same — that’s also selfish, and that’s considered a bad, wrong, unhealthy, religiously or otherwise socially abominable thing.

How do we square this idea of self-preservation as nearly always wrong, with the idea that suicide (i.e. literal self-destruction) is the most morally horrible or psychologically tragic thing a person can do?

To put it bluntly but honestly: If self-sacrifice is such a virtue, why is suicide such a tragedy?

Most of us don’t care to take the time or thought to become this philosophical or “deep.” Yet a depressed person, because of the state he or she is in, tends to ask and consider the tougher questions. That’s part of the reason others consider the person crazy or out of touch. “Why are you worrying about all these issues? Just go about your business and don’t over-think things.”

But maybe the depressed person isn’t able or willing to do that. Maybe the depressed person is hitting on some truths or contradictions the rest of us have been unwilling to articulate, consider or face.

Psychologically, most of us can probably accept the fact that an inner “anti-self” is a bad and ultimately destructive thing. Maybe self-loathing is part of what finally got to Robin Williams and others who follow through with suicide.

If you think about it, a perpetual “anti-self’ inner voice involves a lack of empathy, rationality, compassion and consideration towards the self. If you typically don’t treat yourself well, then how are you to treat others in your life well? How can we expect empathy towards others if we don’t usually display it with ourselves?

Be sure to “friend” Dr. Hurd on Facebook. Search under “Michael Hurd” (Rehoboth Beach DE). Get up-to-the-minute postings, recommended articles and links, and engage in back-and-forth discussion with Dr. Hurd on topics of interest.