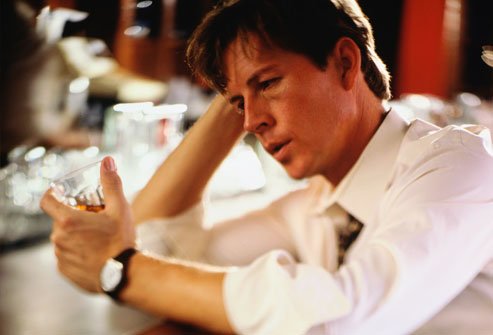

One of the questions I regularly encounter in my office is how a person can approach a loved one or a friend about their drinking without the loved one or friend going on the defensive. Years ago, one of those requests came from a client who was friends with a man who lived alone. Apparently his wife left him at least partly because of his drinking. He became a different person when he drank, and consumed only one meal a day – if that. My client wanted to help get him off the destructive path down which he was headed.

My client was in search of a rational principle to guide her. We psychotherapists are supposed to be ethically and otherwise neutral, avoiding discussion of principles at all costs. But psychological theories are based on very explicit principles, and my answer to her had to be, as well. The first principle that came to mind was: “Ruin and waste your life if you choose, but not with my help.” Obviously my client valued her alcoholic friend, which suggested that he had something to lose or something to waste. If she wanted to speak up, she needed to make her case by telling him what it was she saw in him that he was destroying by living his life the way he was.

Some might believe that the slow suicide of alcoholism is just one big party. It may start out that way, but the truth is that it has nothing to do with the pursuit or attainment of pleasure – in alcohol or whatever. It’s all about avoiding the responsibilities one must take to live a happy and productive life.

That leads to another problem. Many have internalized the idea that an individual’s purpose is to live for others. Achieving things in your own interest, they’ve been told, is not meaningful or important. We’re brainwashed into thinking that it’s only what you give up that matters, and that giving up is a virtue, no matter how it affects us. But how can we even hope to be our brothers’ keepers if we can’t even keep ourselves?

My experience has shown that alcoholics tend to take this misguided philosophy to heart. “If I don’t want to live for others, then my life has no meaning. I’m not a good person. I might as well just drink it away.” This is usually not a conscious or deliberate conclusion, but if motives could speak, that’s what they’d probably say. When people criticize an alcoholic for wasting his life, they usually say, “How selfish of you. Instead of contributing for the sake of others, you self-indulgently live your life for yourself.” More poppycock, and it does nothing but reinforce the alcoholic’s mistaken belief that the primary purpose of life is to sacrifice for others. “That’s right,” he’ll think. “I’m a bad person. Might as well have another drink. What does it matter?” It’s surprising how often I see this sequence of events play out when dealing with the families and friends of alcoholics.

To that end, I suggested to my client that she suggest to her friend that it pains her to see him so selflessly – yes, selflessly, i.e., with no concern for himself – squandering his life. Remind him that he’s really not harming anybody else, unless he does something to physically harm someone (driving while drinking, for example). But he is most definitely hurting himself. That kind of selflessness is the root of most harm people end up doing to others.

My friend eventually provoked him by talking to him about this issue. She did everything she could to convey the outlook that his life and health should be supremely important to him. She reminded him the only reason she was expressing concern was because she saw his potential slowly wasting away.

She returned to see me a few months later. And, surprise, surprise, after her prodding, he had checked himself into rehab. Did she save him? I’ll never know. But at least I was able to help her convince him to try.

Be sure to “friend” Dr. Hurd on Facebook. Search under “Michael Hurd” (Rehoboth Beach DE). Get up-to-the-minute postings, recommended articles and links, and engage in back-and-forth discussion with Dr. Hurd on topics of interest. Also follow Dr. Hurd on Twitter at @MichaelJHurd1