Don’t you believe in flying saucers, they ask me? Don’t you believe in telepathy? — in ancient astronauts? — in the Bermuda triangle? — in life after death?

No, I reply. No, no, no, no, and again no.

One person recently, goaded into desperation by the litany of unrelieved negation, burst out, “Don’t you believe in anything?”

“Yes,” I said. “I believe in evidence. I believe in observation, measurement, and reasoning, confirmed by independent observers. I’ll believe anything, no matter how wild and ridiculous, if there is evidence for it. The wilder and more ridiculous something is, however, the firmer and more solid the evidence will have to be.”

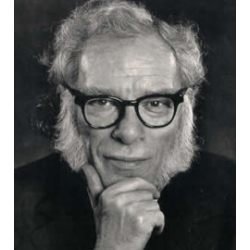

— Isaac Asimov

“I believe in evidence.” Isaac Asimov nails the essence of psychological health … in a single sentence.

The only thing to believe in is evidence and, where warranted, proof. But there is no proof without evidence. Logic has nothing to work with, in the absence of evidence. “Belief,” strictly speaking, is not required for evidence. Evidence rests on the observation of the senses, combined with abstract logical reasoning.

This is not only a concern of scientists. It’s a concern of anyone attempting to think and make decisions pertaining to everyday life. People can distort truth using the observation of their senses. They can point to an observed fact and then draw conclusions from that fact, conclusions which leave out other relevant facts. People do this all the time.

For instance, “Joe left his wife because he was having an affair. His wife Mary is devastated.” Based on these facts alone you’ll conclude, “Poor Mary! And what a lousy character that Joe is.” Perhaps. But what if crucial facts were left out? For example, the fact that Mary had an affair the year before and asked Joe’s forgiveness, which he initially granted? Your attitude will change, because your reasoning and conclusions will change as new facts are brought to light.

Of course, people will sometimes leave out relevant facts because they wish you to form a particular conclusion that you would not otherwise form, without those additional facts. This happens every day. Sometimes it “feels good” for people to believe things without evidence. Believing in telepathy or ancient astronauts might make life more interesting, or perhaps provide hope that you can wish things into existence without rational behavior and thought.

In order to experience this positive emotion, belief in the absence of evidence (or in contradiction of evidence) is developed and maintained. I label this a psychological problem based on a philosophical error. To a person whose only “belief system” consists of reasoning and evidence, there’s no temptation to make things up in this way. It’s not appealing, to a rational person, “just to believe” in the absence of evidence. The minute you try to do so, you experience cognitive dissonance, if you’re a rational person. “But there’s no evidence for this. How can I be excited about something if it isn’t necessarily or even possibly true?”

Some people will never experience this dissonance, which is why they make life decisions—sometimes major ones—in the absence of evidence, or contrary to evidence. Proof and evidence are not just for science. They’re for all of life. You evade or ignore them at your own peril.

Cognitive psychologist Dr. Aaron Beck stated that man is a practical scientist, even in his everyday life. Or, at least: he should be.

Be sure to “friend” Dr. Hurd on Facebook. Search under “Michael Hurd” (Rehoboth Beach DE). Get up-to-the-minute postings, recommended articles and links, and engage in back-and-forth discussion with Dr. Hurd on topics of interest.