Dear Dr. Hurd,

A few weeks ago my wife returned home from the hospital after a serious surgical procedure. My wife and I are happy that she is making a swift recovery but there is one thing that has got us down. We both feel that my wife’s best friend could have done a lot more to be there for my wife at her time of need. After my wife returned from the hospital we didn’t hear from her for two weeks. We thoughtfully composed and sent an email to my wife’s friend letting her know how hurt we are that she was out of contact.

The next day I got an angry call from this friend’s husband. He told me that friendship is not about ‘keeping score’ and ‘punching the clock.’ My wife and I feel crummy and let down. Can you help us to understand what friendship is really about? Did we have unreasonable expectations of our friend? Was it a mistake to send that email?

My reply:

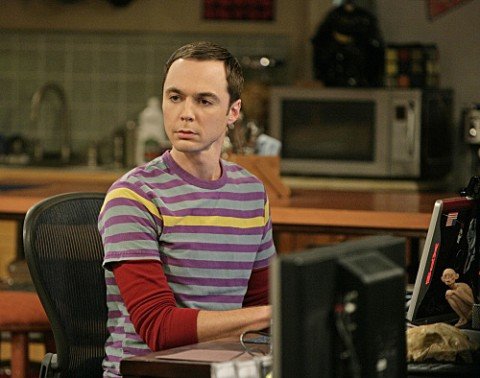

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the witty and smart television comedy series, ‘The Big Bang Theory.’ One of the characters in that show, Sheldon, actually makes his friends sign contracts before becoming friends. He refers to sections of those contracts all the time.

It seems absurd, but there’s a bizarre form of wisdom in the whole thing. If people who are friends made themselves sit down and agree upon contracts ahead of time, then surprises and disappointments—down the road—would be much more infrequent, wouldn’t they?

If your wife had written such a contract along with her best friend, she would have placed something like this into it: ‘When one friend is hospitalized for a serious problem, the other friend will, at a minimum, call and offer to help out.’ If the contract had been made, then she’d be in violation of it now, and you wouldn’t have to write me to ask what—in effect—is right or wrong for friends to do! Sheldon on “The Big Bang Theory” might not be as absurd as we laughably think he is.

Based on my knowledge, there are two possible explanations for your wife’s best friend’s behavior.

One is lack of comfort with illness. Most of us have never been sick, at least not seriously so. We all know that sooner or later we’re going to get sick and eventually die. The rational approach seems not to dwell on it. When a friend gets sick, it seems easier, to some, to simply back away, so as not to confront the unpleasant reality that we’re all subject to serious illness, even life-threatening illness, at any time or age.

The other possible explanation is that your wife’s friend is busier than she should be. It’s possible that she goes through life saying ‘yes’ to things that she shouldn’t be saying ‘yes’ to, or doesn’t even want to say ‘yes’ to. Or, maybe she’s very ambitious and productive, and consequently says yes to a lot of things before realizing she’s in too deep. Whatever the specifics, it’s my observation that a lot of people are trying to do more than they can realistically do. They fail to take into account the old saying about how it’s better to do one or a few things well, rather than lots of things inadequately. As a result, such a person gets so absorbed in being overwhelmed that a friend’s illness seems like—well something that somebody else can handle, and anyway, I’m so busy. It seems like irrational denial to you, because you and your wife have been confronting this crisis head-on, without so much (I gather) as a phone call or a hospital visit, or an offer to help out in some way, from her best friend. But maybe her best friend is doing a lot of things inadequately: Including being a friend.

Other explanations are possible. But either one of these, or both of these, could be factors, and they’re the most likely factors based upon my own knowledge and experience.

Is an explanation an excuse? No. An explanation refers to the cause of a behavior. An explanation, by itself, does not refer to whether or not someone had a choice about something. With either of my proposed explanations, your wife’s friend had the choice to think and act differently.

I don’t know exactly how you worded the letter. I can’t tell you it was a mistake to send it or not, without seeing it. If you had asked my advice before sending it, I would have suggested two things: Try talking it out in person rather than writing it; and I would have encouraged a direct approach but also one providing some benefit of the doubt.

Sometimes, an offense is grave enough that a friendship cannot recover. This might be one of those situations. In other words, if you have to ask for an explanation or excuse for something that seems so obvious to you—then what’s the point?

It sounds like this is how you and your wife might feel. But if you’re still not sure, I would suggest an honest discussion between the two most important parties—your wife and her friend. It’s a little troubling that the friend’s husband is the one who called. He’s really speaking for himself, but not necessarily for his wife in every respect. It seems to me that she should speak for herself, and that your wife and she should have a heart-to-heart talk after this all settles down. It’s all for ‘closure’ if nothing else.

Be sure to “friend” Dr. Hurd on Facebook. Search under “Michael Hurd” (Rehoboth Beach DE). Get up-to-the-minute postings, recommended articles and links, and engage in back-and-forth discussion with Dr. Hurd on topics of interest.