The God gene hypothesis proposes that human beings inherit a set of genes that predisposes them towards spiritual or mystical experiences. The idea has been postulated by geneticist Dean Hamer, the director of the Gene Structure and Regulation Unit at the U.S. National Cancer Institute, who has written a book on the subject titled, ‘The God Gene: How Faith is Hardwired into our Genes.’

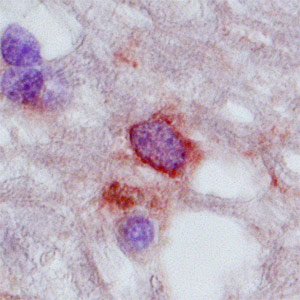

The hypothesis is based on a combination of behavioral, genetic, neurobiological and psychological studies. The major arguments for the theory are: (1) spirituality can be quantified by psychometric measurements, (2) the underlying tendency to spirituality is partially heritable, (3) part of this heritability can be attributed to the particular gene VMAT2, (4) this gene acts by altering monoamine levels in the brain, and, (5) spiritual individuals are genetically favored by natural selection because they are provided with an innate sense of optimism, the latter producing positive effects at either a physical and psychological level.

The hypothesis goes on to say that the God gene (VMAT2) is a physiological arrangement that produces the sensations associated, by some, with mystical experiences, including the presence of God or others.

First, we have to define the concept of ‘spiritual.’ According to the research, spirituality and belief in God are equivalent; you cannot have one without the other. This is what all religions have taught, and what all of them want you to believe.

It’s important to point out how these researchers are also studying something other than belief in God. Their measurements of spirituality are based on a ‘self-transcendence’ scale. This scale, based on research by psychologist Robert Cloninger, describes and attempts to measure spirituality by three major components: (1) ‘self-forgetfulness,’ as in the tendency to become totally absorbed in some activity, such as reading, (2) ‘transpersonal identification,’ a feeling of connectedness to a larger universe, and (3) ‘mysticism,’ an openness to believe in things not literally provable, such as ESP. Cloninger suggests that taken together, these measurements are a reasonable way to quantify (make measurable) how ‘spiritual’ someone is feeling.

The first two of these measures, self-forgetfulness and transpersonal identification do not require a belief in God or the supernatural. The third measure, ‘mysticism,’ obviously does. Doesn’t this point out how people can be spiritual without believing in God or becoming involved in any sort of supernatural practices? The research minimizes this possibility and takes it for granted that anyone who displays characteristics of spirituality automatically must be ‘mystical’ and supernatural.

More completely defined, spirituality involves a concern with abstract philosophical questions outside the realm of everyday life. It does not follow, however, that abstract questions must automatically be disconnected from objective reality. A supernatural spiritualist will assert that there has to be a realm of reality outside of objective reality.

More rational philosophers such as an Aristotle or an Ayn Rand will assert that there’s only one realm of reality, known as objective reality or existence. Ayn Rand asserted,

‘Existence exists—and only existence exists.’ By the definitions of this very research, she was operating in a highly abstract realm, but she wasn’t divorcing herself from reality. Quite the contrary, she was asserting the primacy of reality, the exact opposite of what supernaturalists in the realm of philosophy and religion often claim.

If a genetic link could be established for the tendency to reason and think in such abstract realms—and this is highly theoretical, at best—it still would not prove that such thinking must necessarily include a belief in God or the supernatural.

Indeed, some philosophers, such as Ayn Rand, were atheists, and many others have been agnostics. These philosophical assertions follow from a certain set of premises held about

the nature of existence, reality and consciousness. It’s the philosophical premises that are determining—not the brain structure or chemical makeup of the individual making them.

A number of scientists and researchers are critical of this theory on the genetic origins of spirituality.

Carl Zimmer, writing in ‘Scientific American,’ questions why ‘Hamer rushed into print with this book before publishing his results in a credible scientific journal.’ In his book, Hamer himself backs away from the title and main hypotheses by saying, ‘Just because spirituality is partly genetic doesn’t mean it is hardwired.’

This is what you call the ‘Big Backpedal.’ To say something is genetic clearly implies that it’s hardwired, doesn’t it? Your eye and hair color, the color of your skin, are all genetically determined. You wouldn’t say, ‘My skin color is genetically determined, but it’s not hardwired.’ This statement is just as ridiculous as Hamer backpedaling his way into the claim that supernatural belief, while genetically determined, is not ‘hardwired.’

Interestingly, one of the assertions of Hamer’s theory is that spiritual individuals are favored by natural selection. Natural selection refers to ‘survival of the fittest.’ The strongest will live another day to reproduce more like themselves. Those best equipped biologically to survive and flourish are the ones who continue living, genetically and biologically speaking. There is much in reason and science to support natural selection.

If the ‘God gene’ applies to natural selection, then this would imply that believing in a God (as most people do) favors the perpetuation of the species. Yet the bloodiest, most violent conflicts throughout human history—up through and including the fundamentalist Islamic attacks on secular human civilization—are grounded in belief in the supernatural. Put bluntly, the more fervently human beings tend to believe in the supernatural, the more viciously they will kill. The greater the belief in a supernatural God, the more intense the hatred and violence against those who dare to disagree. How can these two factors be reconciled if belief in God is so life-sustaining? No answer will be given, because the question is not even asked by the researchers.

Ironically, prominent advocates of religion and the supernatural are not inclined to agree with the genetic theory of a belief in God.

John Polkinghorne, an Anglican priest and member of the Royal Society and Canon Theologian at Liverpool Cathedral in England, was asked for a comment on Hamer’s theory by ‘The Daily Telegraph,’ the British national daily newspaper. He replied, ‘The idea of a God gene goes against all my personal theological convictions. You can’t cut faith down to the lowest common denominator of genetic survival. It shows the poverty of reductionist thinking.’

In this context, reductionist thinking refers to genetic determinism, i.e., the viewpoint that genes determine everything. Objectively speaking, there is more to life than genes and biology. Our genetic structure, including our brains, are metaphysical ‘givens,’ and science is right to study these existential givens so that we may better understand ourselves, cure diseases, and so forth. However, you cannot claim to know everything there is to know about a person while ignoring his choices, his convictions, his chosen values, his emotions, his integrity (or lack thereof), his philosophy of life (however implicit or contradictory), and all the other things that make up what might rationally or religiously be referred to as ‘the soul’—or the human consciousnesses.

Concluded in tomorrow’s column.