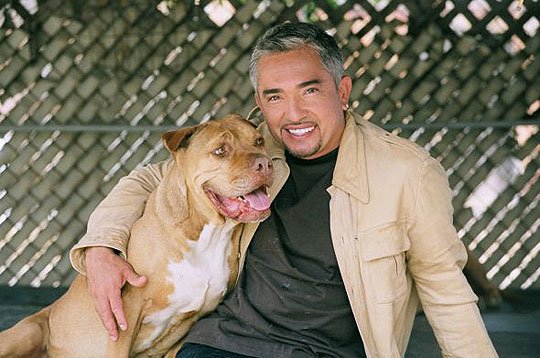

When it comes to child psychology, I much prefer Cesar Millan — “The Dog Whisperer” — to the mental health establishment.

Millan is a dog psychologist, but he’s more of a human one than you think. In case you haven’t seen Millan’s show, he operates on more rational assumptions than do most human psychologists. He understands the behavioral and mental make-up of dogs quite well, but he also grasps that most of the behavioral problems exhibited by dogs are the result of problems involving the humans.

Over the seasons of his show (and I have watched them all), Millan has helped viewers correct errors in thinking. For example: ‘Dogs are not your children; they’re dogs.’ You cannot project human feelings on to them and then respond to those feelings in what you consider to be a rational way. Dogs are looking for love, but also for leadership. They instinctually need you to be “the top dog” because this is germane to their very survival.

Behavioral problems in dogs develop when humans go awry. For example, a highly anxious woman in a recent episode began to cry as she talked about how stressful her life was. Cesar did not attempt to help her with her own problems, but he did point out that her anxiety was being conveyed to the dog. His comment was that an anxious human almost always leads to an anxious dog. Dogs are just picking up on the emotions of the humans around them. Millan calls this “energy,” his somewhat vague term for the behavioral and other cues humans give off — on the perceptual/sensory level — that dogs pick up on. Do dogs cognitively understand what the anxiety of emotion is? No. But dogs sense it nonetheless, from various nonverbal cues or even scents the human gives off.

The Dog Whisperer is valuable in two respects: One, for the help and ideas he can give people with their dogs; and two, for his sensible illustration of the role humans play in the perpetuation of the dog’s problems. This latter is something that human/child psychologists almost never do. With human children, the premise of the parent (and encouraged by the professional) is: Something is wrong with the child and the child needs “treatment,” which is to say — fixing. This removes all responsibility from the parent, even for doing something unintentionally counterproductive or harmful to the child; and it simultaneously removes all responsibility from the child.

This explains the popularity of medication to fix children’s problems, despite its elusive effectiveness. “Oh, good,” the parent thinks, and is encouraged to think by the mental health and medical establishment. “It’s not me. And it’s not Johnny either. It’s something completely external, like the flu.” In practice, of course, medication rarely does what parents hope it will do, and never entirely solves any behavioral problem in a child. But parents hold on to the myth anyway, because the alternative — that the child or even the parent him- or herself might be part of the problem — is unthinkable.

None of this baloney is present on The Dog Whisperer. Cesar Millan is very nice and personable, but there’s no question that he understands — and expects his dog owner clients to accept — that whatever behavioral problem the dog is displaying, it’s almost certainly due to something the “doggie parent” is doing, however unintentionally. He exposes errors in thinking, such as the false belief that “the doggie is my child” rather than the objective fact that the dog is a DOG — that a dog has a certain nature, a certain set of instincts, and you have to work within those parameters. Dogs absolutely need limits and boundaries. They don’t “get their feelings hurt” so much as experience anxiety when the dog owner is a less than effective “pack leader.” Dogs of course don’t want or need neglect or abuse. But inconsistency or lack of boundaries are just as damaging.

Wow. This all sounds just like young children!

Children are not dogs, in that they are growing into conceptual beings that dogs will never be. Children are human, and humans do not survive by instinct — they survive by reason. However, domesticated dogs (who are not wolves) survive in great measure by the reason of human beings, which is why they relate to humans so well, as compared to wild animals. And children share in common with dogs a heavy reliance on the sensory-perceptual level of consciousness.

This is because young children have not yet developed into sophisticated conceptual thinkers. Very young children are very responsive to the cues, behaviors, and other sensory cues of adults, because in the absence of advanced thinking this is most of what they have.

Children need and want leadership without really grasping what those concepts are. Yet when the parent of a behaviorally troubled child goes to a child psychologist, the parent does not get Cesar Millan. Instead the parent is usually told that the child is “acting out” which, in plain English, means that the child is not responsible for any of his actions — nor is the parent — and that the solution is undefined “treatment.”

In the old days “treatment” consisted of unexplained psychotherapy, usually with the child alone, which the child could not comprehend, could not be explained to the parents and perhaps the psychotherapist himself did not fully understand. Today, it’s simpler in that the child is given a pill. Does the pill work? No matter, because the parents only get five minutes maximum with the prescribing psychiatrist anyway and the alternative to medication if the problem isn’t biological in origin is … unthinkable.

A better solution for parents would be what Cesar Millan does with dogs. He frankly and objectively proves to “dog parents” what’s mistaken in their thinking or actions, and how those errors have an impact on the dog’s behavior. It basically boils down to leadership. The answers are not always simple or obvious, but going on this correct premise almost always leads to positive results because the theory is in contact with reality. Parents are shaping their kids more than they know, at least while those kids are still kids; if there’s a problem with the child, the parent must take the lead in whatever the solution is.